AI’s Ultron Moment – Johansson Takes on OpenAI Over Uncanny Voice Resemblance

You’ve heard of a lookalike, but have you heard of a soundalike?

The Aural Uncanny Valley: it’s something that sounds the same as something else, but is just not quite right. New generative AI (gen-AI) tools have boldly gone where no human has gone before, using AI-generated voices to create song covers by your favourite artists, deepfakes (are we the only ones who’ve seen Ice Spice and Joe Biden explaining differential calculus on TikTok?) and providing assistive communication tools for people at risk of losing the ability to speak.

Digital assistants, however, have been with us for a while now in tools we use every day – Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa, for example. But, they tend to give stilted answers, and sometimes can’t do much more than tell you the weather or turn the lights on or off.

More recently, OpenAI really upped the ante, powering up its gen-AI platform ChatGPT with a new “Voice Mode” that can giggle, hesitate, joke, sing and converse with users. But, as some astute users noticed, one available voice called ‘Sky’ sounded uncannily similar to the voice of Scarlett Johansson – an eerie simulacrum of Ms Johansson as the AI assistant ‘Samantha’ in 2013’s film ‘Her’ – leaving the actress herself “shocked” and “angered” at the similarity. Is legal action now imminent?

How did we get here?

Based on a public statement from OpenAI:

- In early 2023, OpenAI had partnered with casting directors and producers to create job ads for voice actors.

- In June and July 2023, OpenAI conducted recording sessions and in-person meetings with the five selected voice actors.

- In September 2023, OpenAI’s CEO, Sam Altman, contacted Scarlett Johansson directly to see if she might be interested in contributing as a voice actor in addition to the existing five voices. Ms Johansson declined the offer.

- On 25 September 2023, OpenAI released voices for ChatGPT.

- On 10 May 2024, Altman contacted Ms Johansson again to ask again if she might wish to contribute as a voice actor in the future.

- On 13 May 2024, OpenAI released their newest AI model GPT-4o, giving access to a new ‘Voice Mode’.

- On 15 May 2024, OpenAI began discussions with Ms Johansson regarding her concerns over the “Sky” voice.

- On 21 May 2024, OpenAI confirmed that it would remove the Sky voice, but maintained the voice was not intended to be an ‘imitation’ of Ms Johansson’s.

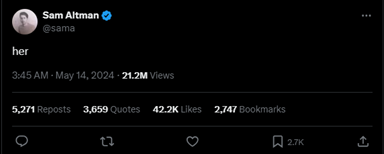

Separately, on 13 May 2024, Altman posted the word ‘her’ on X (formerly Twitter) – a move many online considered to be an allusion to the 2013 sci-fi/romance movie by the same name, starring Ms Johansson.

Possible Legal Issues and Claims – an Australian perspective

Although this dispute probably won’t make its way to the courts, these kinds of issues look set to become increasingly prevalent as gen-AI tools get better at generating synthetic voices that traverse the ‘Uncanny Valley’ for commercial (or personal) use. This would likely raise several intellectual property and consumer law concerns in Australia.

Let’s play this out in the current fact situation (remembering that Ms Johanssen would only need to win on one type of claim to take the prize):

- Copyright in voices

Some people have suggested that this matter might be dealt with by copyright law. However, we doubt that would be the case in Australia.

The Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (Copyright Act) provides protection of original expressions of ideas and information in ‘material’ form – for instance, something written down, an image, a sound recording or video recording, or a computer program.

This focus on a ‘material form’ means the Copyright Act would be of little use to someone trying to claim copyright over their voice per se. However, a claim could succeed to the extent a person might claim a recording of their voice was used without authorisation. However, it would be the copyright in the recording – not the voice itself – that would be protected in that case.

- Voices as trade marks

Australian trade mark law permits the registration of auditory trade marks. The challenge, however, is that section 40 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) provides that applications for trade mark registration must be rejected if the trade mark cannot be represented graphically.

This is generally not an issue for trade marks that can easily be represented by a word, logo, musical notations or, in some cases, visual representation of a product – provided that the other registration requirements (such as the trade mark distinguishing a particular good or service)[1] are also met.

As IP Australia notes, representation of a sound in words requires considerable explanation – such as:

“The trade mark consists of a repeated rapid tapping sound made by a wooden stick tapping on a metal garbage can lid which gradually becomes louder over approximately 10 seconds duration. The sound is demonstrated in the recordings accompanying the application.”

This cannot easily be done for a voice, as it is challenging to set out the unique characteristics of a voice in words or graphics. Because of this, it is unlikely that trade mark law could come to the rescue of an aggrieved celebrity looking to protect their voice from use by gen-AI tools.

- Consumer law breaches from misappropriating a voice

The Australian Consumer Law[2] prohibits conduct in trade or commerce, that is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.[3] It also prohibits the making of false or misleading representations that goods or services have testimonials, sponsorships or approvals from a person, that they were created with the assistance or contribution of a person, or that they have any other affiliation with a person, when that is not in fact the case.[4]

The intention of the law is to protect the public from false, deceptive or misleading claims by traders about their products, services or businesses. These can include false representations regarding endorsements of products, services or businesses from a celebrity such as Ms Johansson which could otherwise mislead a consumer.

In March 2024 the ACCC issued a warning to consumers to beware of ‘fake news articles and deepfake videos of public figures that endorse and link to online investment trading platform scams.’

But the issue goes beyond scams. In 1989, Paul Hogan successfully sued a shoe manufacturer for its adaptation of the famous “That’s not a knife” scene from the movie Crocodile Dundee, alleging that the manufacturer had falsely represented that the shoes (or the manufacturer) had an affiliation or approval from Paul Hogan that they did not actually have.[5]

If a claim were brought in Australia, Mr Altman’s post on X of ‘her,’ coupled with the similarity of the (now removed) ‘Sky’ voice to Ms Johanssen’s could form a basis for a claim under the Australian Consumer Law, alleging that OpenAI was attempting to suggest:

- a celebrity endorsement by Ms Johansson;

- the involvement of Ms Johansson in the creation of OpenAI’s synthetic voice; or

- that Ms Johansson was otherwise affiliated with the synthetic voice.

But the real issue for the vast majority of us is that we are not celebrities, and though Ms Johanssen might be successful, it will be her fame that likely gets her over the line. You and I might not have the same success in similar circumstances.

Managing gen-AI risks going forward

In all likelihood, if this case were brought in Australia, Ms Johanssen would score a win, based on the Australian Consumer Law. Some commentators have also suggested that from a public relations perspective, this turn of events appears to be a massive own goal by OpenAI, undermining relationships with creatives and the public’s trust. On the other hand, there is no denying that the gen-AI-world has been talking about ‘Sky’ and OpenAI’s GPT-4o – an outcome the company may have been hoping for all along.

Whether you’re a hotshot gen-AI startup, or a celebrity looking to protect your valuable voice and likeness, you should be paying careful attention to how you obtain or provide consent and/or licences to your valuable IP. In particular:

- Obtaining or providing clear, express consent will help remove ambiguity about when you can use (or have agreed to share) intellectual property rights that can be claimed over a voice; and

- Entering into a robust licensing agreement will clarify the terms on which that voice can be used – helping mitigate the risk of claims for misuse down the line.

However, this may be little comfort to a celebrity who just wants to make sure their voice or likeness is not misused – either to misrepresent what they stand for, or to mislead the public.

A statutory regime?

Australia doesn’t have a law specifically regulating the use of AI. Rather, the best we have so far is Australia’s voluntary AI Ethics Framework. That framework sets out helpful principles such as a ‘benefit to society,’ ‘human-centred values’ and ‘fairness’, but does little to compel compliance.

The Australian Government has this issue on its radar, with public hearings for the Senate Select Committee on Adopting Artificial Intelligence held from 20-21 May 2024. Similarly, the Department of Industry, Science and Resources is reviewing responses to the Supporting responsible AI: discussion paper.

However, there remains a gap in regulation where AI users can potentially use (or misuse) individuals’ voices or likenesses without consent. The present legal framework doesn’t really help, beyond some limited consumer protections. Care must be taken to ensure any future regulation is sufficient to protect individuals from this misuse, while continuing to provide a regulatory environment that still permits innovative technologies like gen-AI to flourish.

While time will tell for the Australian AI regulation journey moving forward, we might just be in for Ms Johansson’s greatest battle against AI since taking down Ultron in her role as Black Widow.

If you found this insight article useful and you would like to subscribe to Gadens’ updates, click here.

Authored by:

Antoine Pace, Partner

Chris Girardi, Lawyer

Raymond Huang, Lawyer

[1] Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 41.

[2] Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) sch 2.

[3] Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) sch 2 s 18.

[4] Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) sch 2 s 29.

[5] Pacific Dunlop Limited v Hogan [1989] 23 FCR 553.