Casual IR reforms – A new frontier for employers

On 9 December 2020, the Attorney-General and Minister for Industrial Relations, Christian Porter introduced the Fair Work Amendment (Supporting Australia’s Jobs and Economic Recovery) Bill 2020 (IR Reform Bill) to Parliament, which sought to make significant reforms to the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) and other related legislation.

The IR Reform Bill was drafted following six months of round table discussions with key stakeholders from employer, employee and industry groups, to address the surge in unemployment due to the COVID-19 pandemic and issues highlighted by recent Federal Court decisions. It has been the most controversial workplace bill tabled since the Howard Government’s ‘WorkChoices’ reforms in 2005.

The IR Reform Bill initially proposed changes to five key areas, including casual employment, part-time employment, enterprise agreements, underpayments and wage theft, and greenfield enterprise agreements. However, in a final attempt to get the Bill passed by Parliament prior to it adjourning until May 2021, the Coalition abandoned all proposed reforms, except those relating to casual employment.

The reforms in relation to casual employees were re-introduced directly in the Senate under the amended Fair Work Amendment (Supporting Australia’s Jobs and Economic Recovery) Bill 2021 (Casual IR Reforms) and were passed by the Senate on 18 March 2021, before being sent back to the House of Representatives for consideration. Although the opposition attempted to reinstate the non-contentious provisions of the original IR Reform Bill that related to wage theft, the Casual IR Reforms were passed without difficulty on 22 March 2021. The Casual IR Reforms will commence on the day after the Act receives the Royal Assent.

What are the key changes?

The Casual IR Reforms include four changes in relation to casual employment, which are intended to clarify the proper classification and entitlements of casual employees and broaden the process for making a claim.

Statutory definition of a casual and ‘double dipping’

Of most significance in the Casual IR Reforms is the insertion of a statutory definition of a ‘casual employee’ into the FW Act. This definition is intended to remove uncertainty and concerns about ‘double-dipping’, which arose as a result of employees who were misclassified as casuals and subsequently claimed entitlements as ‘permanent’ employees, as seen in the recent decision of WorkPac v Rossato (Rossato),[1] for which the High Court has since granted leave to WorkPac Pty Ltd to appeal the decision (see our previous article).

To complicate the legal position concerning casual employees further, awards and agreements have tended to adopt artificial definitions of casuals, such as someone who is engaged and paid as such and/or works less than a set number of hours per week. Where these definitions applied, it was irrelevant whether they were hired for a limited purpose or period, or indefinitely, and in practice such employees were often engaged for long periods of time.

In Rossato, the Federal Court considered that the central question as to whether a casual employment relationship exists, is the absence of a ‘firm advance commitment’, characterised by irregular work patterns, uncertainty, discontinuity, intermittency of work and unpredictability. This in contrast with a ‘permanent’ employee who is engaged on an ongoing basis.

It highlighted that many Australian employers have failed to adopt practices of critically assessing their models for engaging casual employees and/or revisiting arrangements over time, to consider if some casuals would be more appropriately classified as permanent staff and whether there is any real benefit to the business in employing casuals over permanent employees.

In this case, the risks for employers regarding misclassified employees and the payment of permanent entitlements was also emphasised. The Federal Court determined that WorkPac Pty Ltd was not entitled to set off any payments made to Mr Rossato on the basis that casual loading is not a substitute for taking actual time off, as an entitlement to paid time off is not just a monetary entitlement, but rather an entitlement to be absent from work without the loss of pay.

In response to the concerns of employers around this decision and the double dipping implications it raised, the Federal Government introduced the Fair Work Amendment (Casual Loading Offset) Regulations 2018 (Cth) (Offset Regulations) which took effect from 18 December 2018.

The Offset Regulations clarified for employers that, in certain circumstances, they may make a claim that an employee’s casual loading payments should be offset against entitlements found to be owing to the employee where the employer can satisfy certain criteria.

The introduction of the definition of a ‘casual employee’ in the Casual IR Reforms, in effect contradicts the decision in Rossato. The new statutory definition captures an employee as a casual if the employee accepts an offer of employment that makes no firm advance commitment to continuing and indefinite work, according to an agreed pattern of work. The true nature of the engagement will be assessed on the manner in which the offer of employment is made and accepted, and not any subsequent conduct.

A regular pattern of hours will not of itself indicate a firm advance commitment by an employer of continuing work, instead regard will be given to whether the employment is specified as casual and entitled to a casual loading, and the employee can accept or reject work and can work only as required.

An employee should no longer be able to ‘double dip’ where they have been misclassified as casual. The Casual IR Reforms makes it clear that employers can offset or deduct any loadings already paid to employees deemed to be employed on a casual basis against current or future claims for permanent employee entitlements.

Casual conversion

Prior to the Casual IR Reforms, many employees had a right to elect or request conversion to full-time or part-time employment under applicable awards. The Casual IR Reforms include a statutory obligation on employers, except small business employers, under the NES to make an offer to casual employees to convert to ‘permanent’ employment, where they have been employed for 12 months and have worked a regular pattern of hours on an ongoing basis for the preceding six months, unless there are reasonable grounds, similar to those currently available under the awards, not to.

If an employee declines an offer of conversation, as long as they remain eligible, they may request conversion every six months, however, an employer can refuse on reasonable grounds or where it would require a significant adjustment to the employee’s hours of work.

Applicable employers should be aware that where there is a casual conversion provision in a relevant award that differs from or contains greater obligations than the NES provision, the award must be complied with in relation to applicable employees, and periods of casual employment will not count towards the accrual of notice, paid leave, or redundancy entitlements.

Casual Employee Information Statement

For each employee engaged by an employer, there is now the obligation to provide the casual employee with a copy of the Fair Work Ombudsman’s ‘Casual Employee Information Statement’ at the commencement of their employment. This requirement is similar to the current obligation on employees to provide all Federal system employees with a Fair Work Information Statement.

Small Claims Procedure

Under the Casual IR Reforms, employees may make an application to a magistrate or the Federal Circuit Court for an order that is not a financial penalty, relating to whether an employer, that is not a small business employer, must make an offer or grant a request to its casual employee for conversion to permanent employment or preventing an employer from relying on an unreasonable ground for not offering or refusing a request for conversion.

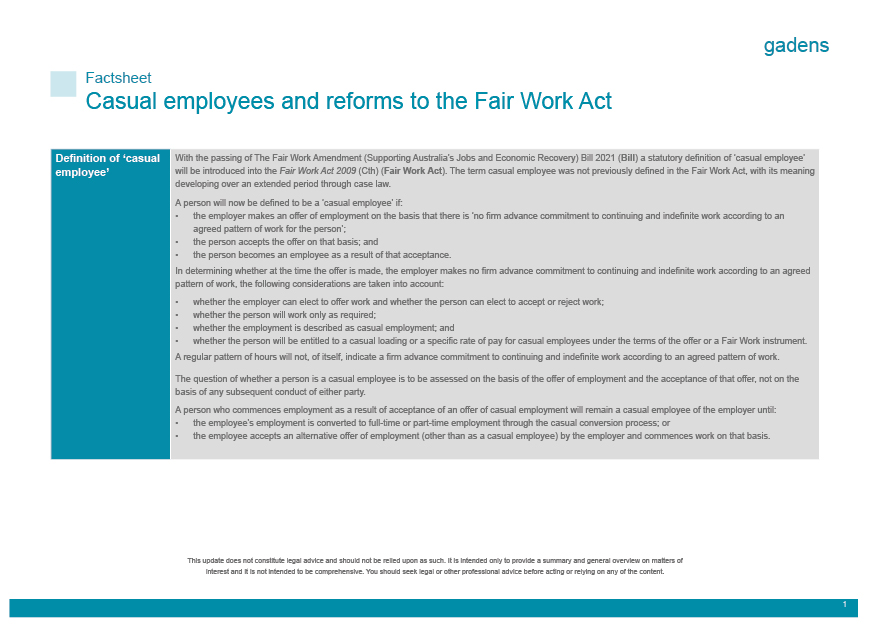

Click below to view our easy-to-download factsheet: Casual employees and reforms to the Fair Work Act.

What employers can do?

Now that the Casual IR Reforms have been passed, we would recommend that employers do the following:

- Review established casual positions which require the regular long-term engagement of the incumbent for the position’s suitability for conversion to part or full-time employment.

- Develop a process to manage the engagement, or conversion, of casual employees, including updating casual employment agreements or letters of offer to factor in the new casual definition and obligation to offer conversion to eligible casuals.

- Review set-off clauses in your employment agreements to ensure consistency with the new restrictions on ‘double-dipping’ of entitlements for misclassified employees.

- Review the projected future requirements of your business operations which are currently being carried out by positions currently classified as casual.

- Consider further education of those responsible for hiring staff, to ensure that they are aware of the casual definition, requirements for casual conversion and the need for a Casual Employee Information Sheet for each casual employee engaged by the business.

If you require assistance in navigating these changes, please contact Gadens’ Employment Advisory Team.

Authored by:

Brett Feltham, Partner

Jonathon Hadley, Partner

Sarah Toohey, Partner

Ross Wilson, Senior Associate

Lisa Carey, Associate

[1] WorkPac Pty Ltd v Rossato [2020] FCAFC 84.